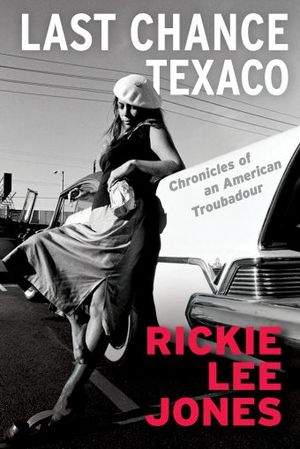

The iconclastic singer-songwriter Rickie Lee Jones recently released a memoir, Last Chance Texaco: Chronicles of an American Troubadour—borrowing her own evocative song title. It’s been almost 10 years since I interviewed Rickie for VanityFair.com. I haven’t read the memoir yet, but one reviewer called it lyrical and I’m not surprised; during our time together she spoke poetically, colorfully, candidly. We met at Café Henri (since closed) on Bedford Street in the West Village, near where I live. Rickie was wearing pastel sweatpants, a loose top, and no discernible makeup—as though anticipating our pandemic time. This was quite a contrast to her self-described early look of “a stripper and German cabaret dancer” (though it’s not as if we were doing a photo shoot!).

Rickie Lee Jones and I backstage at City Winery in NYC. Photo by Robert Rosen.

I wondered if she was feeling strange at all about her (fantastic) concert at City Winery a couple of nights before. She had started almost an hour late, and during her lingering song introduction for "Weasel and the White Boys Cool," a woman in the audience yelled out, “This is what we’ve been waiting for?” Rickie answered with an obscenity, left the stage, came back, and calmly said she was going to pay for the woman’s (pre-show) dinner and the security people would see her out. But at Café Henri, I didn’t detect any leftover anger, and when Rickie brought up the incident, she spoke of the woman compassionately, saying maybe she had had a very bad day.

In the middle of the interview, Rickie suddenly commented on my eyes—that they looked like her mother’s and maybe we were related. This was surprising and touching. (I edited it out of the written interview, but when I mentioned it to the editor he loved it and said to put it back in.) In the years afterward Rickie and I exchanged a few emails. In one she wrote: “It’s a big country for us, we work in language and there is no locality for that, so we are connected to people thousands of miles away as much or more than people round the block. We have to construct our neighborhood nowadays, I guess, make our roots out of events rather than locations.” Like her comfy outfit, this seems prescient now.

In a new memoir, the singer explores the wild ride of her youth.

At the time I met with Rickie, her fame had dimmed somewhat, at least among the general populace. I can see her across from me at our little café table by the window, her blond hair falling around her shoulders, a kind of natural gravitas settling over her. She made a reference to a time, a hard time for her, when “everywhere I went people knew me,” and I could peripherally see the young woman at the next table trying to stare at Rickie without being obvious: Who was this middle-aged person who had once been famous? There weren’t many people in the café, but no one stopped at our table. I don’t think Rickie was recognized. But lately she’s been more in the public eye, especially on social media—at times walking her audience through her place in New Orleans, which in its décor reflects the mysterious magic of that city (come to think of it, is there a better place for her?); at other times performing a concert in her living room or at a local outdoor venue. Occasionally, I’ve tuned in to a Facebook Live hello from her and marveled at the way she spontaneously conjures vivid images and ideas, all with a relaxed smile.

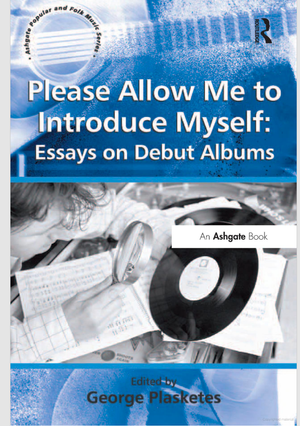

About a year ago I discovered that quotes from our Vanity Fair interview had appeared in the somewhat scholarly book Please Allow Me to Introduce Myself: Essays on Debut Albums, edited by George Plasketes. I was thrilled, as this had never happened to me before—I scoured the pages for “(Maiscott 2011)”!—and I was in the company of such esteemed music critics as Timothy White and Stephen Holden. In writing of Rickie’s first, eponymous album, the author referred to my characterization of the singer as “Billie Holiday on a rock bender” as well as Rickie’s “stripper look” remarks and her explanation of what I called her slurry sounds (“It was more important to round it out than to make sure you knew what I was saying.”)

Quotes from my Vanity Fair Q&A with Rickie appear in this book about first albums.

I have read the very beginning of her memoir, and in it Rickie speaks of being in “a perpetual state of fear and longing” as a child, and how this has formed the background of many of her songs. And that is why I think she is our perfectly imperfect troubadour, her works reflecting our own fear and longing back at us like so many gems—ones that shine as though they might be our last, best chance.